The Washington Post: Apparent crackdown in Vietnam on social media, but many users undeterred

Vietnamese activist Anh Chi searches the Internet at Tu Do (Freedom) cafe in Hanoi. REUTERS/Kham (Kham/Reuters)

By Vincent Bevins

HANOI — The police in communist-led Vietnam have been cracking down especially hard on free expression over social media for the past few months.

Or, at least as far as experts, regular users and dissident bloggers can tell, that seems to be the case.

“Even activists in Vietnam struggle to say how many people are actually caught and arrested” for online activity, said Janice Beanland, a campaigner at Amnesty International. “But one striking thing is that Vietnamese activists seem not to be deterred.”

Vietnam doesn’t have the resources of its big neighbor to the north to maintain a “great firewall” or its own social media platforms. So Facebook and other global social networks are popular here. They are filled daily with all kinds of political speech, including quite direct attacks on the government. Vocal users wonder whether their output is being watched, and rumors swirl about shutdowns or hacking.

It’s not clear to anyone on the Web here exactly what the rules are, leading some to question whether Vietnamese censorship is haphazard and counterproductive or part of a more considered strategy to create an efficient chilling effect.

Those who take free speech too far risk harassment or arrest. But how far is too far?

“It’s getting more difficult for us. Why? Some people say that Donald Trump doesn’t care about human rights, and so the [Vietnamese] Communist Party feels more free. I don’t think that is the full answer,” said Nguyen Chi Tuyen, known as “Anh Chi” online, one of the country’s most prominent dissidents now that two of his peers have been handed long prison sentences. “They also want to threaten a younger group which is thinking of following us.”

He was sitting in downtown Hanoi, at a self-declared “hipster” cafe decorated with tongue-in-cheek celebrations of the North Vietnamese communist forces that defeated the United States 40-some years ago. Downstairs, well-dressed Vietnamese youth clacked away on Apple products.

“I am safe at this cafe now,” he said, looking around. “But I have been arrested more times than I can count and could go to jail anytime.”

There are many users, nonetheless, who have not been slowed by the uncertainty.

“I used to be a little afraid [of getting in trouble], but not anymore,” said Luke Nguyen, a real estate investor, sitting in an upscale Ho Chi Minh City cafe. He showed a piece of sexually explicit satire he recently posted publicly about the case of Trinh Xuan Thanh, a former Vietnamese oil executive Germany said was abducted by his own country in Berlin. “Because I’m just a little guy, not even an activist, just a citizen exchanging ideas.”

This sentiment — you can probably say what you want, as long as you aren’t famous – can be heard often in Vietnam. But Beanland said that even if most of the arrests that get attention are of high-profile dissidents, there may be much more going on that does not make headlines.

“It appears that there have been more arrests recently. But what we hear about may just be the tip of the iceberg,” she said.

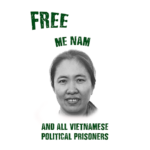

This year so far, Nguyen Ngoc Nhu Quynh, known as “Mother Mushroom,” and Tran Thi Nga, often called Thuy Nga, were given long sentences. Mother Mushroom got 10 years, while Thuy Nga got nine.

Facebook is the social network most often used to express political opinions here, and for many other daily activities as well. New SIM cards in Vietnam often come bundled with free Facebook usage, and many citizens use its Messenger app in lieu of text messages. But it wasn’t always clear that Mark Zuckerberg’s company would play such an important role in the world’s 14th-largest country.

In 2013, then-Prime Minister Nguyen Tan Dung announced the goal of building a homegrown social network for young Vietnamese people. But in early 2015, he acknowledged that it would be impossible to ban social media platforms such as Facebook. “You here have all joined social networks, you’ve all got Facebook up on your phones to read information. We cannot ban it,” Dung told his cabinet members. “We must publish accurate information online immediately.”

Instead, the government has set up its own Facebook page, to keep the public in the loop on new policies or to live-stream monthly cabinet meetings.

“The Communist Party of Vietnam is in a bind,” said Zachary Abuza, a professor researching Southeast Asian politics at the National War College in Washington. “It is committed to maintaining its monopoly of power and, as such, feels threatened by unfettered social media. Yet its Internet is relatively open, and they have nothing like the Great Firewall of China.”

Vietnam’s intermittent censorship doesn’t exist only online; it often appears that the state acts in cyberspace the same way it operates elsewhere. In the capital, it’s quite easy to come across almost clumsy or comical surveillance. At the recent opening night of an art exhibition in Hanoi, a slightly overweight man in casual clothes walked in. “Oh, that’s the spy, he comes to every opening,” said the artists to a group of visitors. “He just eats all our snacks and drinks all the wine and then leaves.”

He proceeded to do exactly that. But censorship is not always a joke for Vietnam’s artists, who say they can have exhibitions shut down for reasons that are never explained to them.

The surveillance extends to sports, as well. The dissident soccer team No-U FC plans the location of its weekly games — on Facebook — just before kickoff to avoid having cops show up to disrupt them. The team’s name is a rejection of the U-shaped delineation of China’s claim in the South China Sea. For dissidents, nationalist opposition to Chinese aggression is their biggest issue.

“I’d like to see electoral democracy, but not everyone I know agrees. But almost everyone I know opposes China. China is less popular than communism,” said Pham Anh Cuong, a member of No-U FC. As he was talking over lunch, he got a Facebook message and burst out laughing. “A friend just saw something I posted criticizing a local official and is asking me to take it down.”

Would he? He laughed louder. “Of course not! Why would I?”

Source from The Washington Post